|

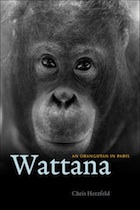

Wattana. An Orangutan in Paris

Chris Herzfeld

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

2016

Translated by Oliver Y. Martin and Robert D. Martin

« She likes tea, sews, draws on papers, and is a self-taught master of tying and untying knots. But she is not a crafty woman of the DIY set: she is Wattana, an orangutan who lives in the Jardin des Plantes Zoo in Paris. And it is in Paris where Chris Herzfeld first encounters and becomes impressed by Wattana and her exceptional abilities with knots. In Wattana: An Orangutan in Paris, Herzfeld tells not only Wattana's fascinating story, but also the story of orangutans and other primates - including bonobos, chimpanzees, and gorillas - in captivity. »

REVIEWS

« Herzfeld offers fascinating reflections on a zoo-born ape and her human cultural context. A must-read for anyone interested in the shifting human-animal boundary - including creativity and the aesthetic sense - as illustrated by an exceptionnally talented orangutan. »

Frans de Waal, author of Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are ?

« If you have ever wondered how smart and sensitive an ape can be, read Wattana, an engaging account of an orangutan who deserves a biography as much as any human subject has ever done. »

Ian Tattersall, author of The Strange Case of the Rickety Cossack and Other Cautionary Tales from Human Evolution

« In this absorbing study, blending science, history, and philosophy in an altogether original way, Herzfeld uses the story of a non-wild ape, the zoo orangutan Wattana, to explore a range of important questions about both sides of the ape-human encounter. Wattana's complexity, and the dignity and interest of lives like hers, are rendered unforgettably. »

Gregory Radick, author of The Simian Tongue: The Long Debate about Animal Language

PRESS

« For this thoughtful, unusual study of the human–ape ‘interface,’ philosopher of science Herzfeld focuses on a captive orangutan, one of less than 1,000 worldwide. Zoo-born Wattana, given string, cloth and paper at the Jardin des Plantes menagerie in Paris, made elaborate knots and ‘necklaces’ — a skilful use of fibre unsurprising in a tree-dwelling primate that builds complex nests, yet so far seen only in captivity. A trove of gripping research. »

Nature, May 2016

« Herzfeld, founder of the Great Apes Enrichment Project, follows the life of an orangutan named Wattana who is housed at the Jardin de Plantes Zoo in Paris. Wattana exhibits a strong interest in human pastimes, thanks in large part to her upbringing among human caretakers after being rejected by her mother. Herzfeld describes how Wattana became a talented and avid knot maker: weaving a variety of materials in and out of her cage bars like a giant macramé project, tying knots in careful sequences, and improvising items when no conventional materials could be found. Wattana appears to derive much pleasure from her creative knot work, just one of several highly human behaviors she exhibits. Herzfeld documents her observations of Wattana while offering historical and scientific information about the great apes, both in the wild and in captivity. Scientists, zookeepers, animal behaviorists, and those with similar credentials will find Herzfeld’s book both fascinating and educational. »

Publishers Weekly, April 2016

« As Herzfeld points out, field primatologists such as Jane Goodall have followed the stories of individual great apes in the wild, but few have shown a similar interest in the lives of the thousands of great apes living in captivity. Herzfeld seeks to rectify this mistake and acts as spokesperson for Wattana, a female Bornean orangutan whom she met at Paris’ Menagerie of the Jardin des Plantes. Wattana is known for her abilities at knot tying, a behavior she apparently picked up on her own. She is also known for her friendliness and interactivity with her human keepers, which facilitated her transfer from Paris to the Apenheul Nature Park in the Netherlands. By following Wattana’s life, Herzfeld also follows the evolving philosophies of how zoos function and changing theories on the care of exotic animals in captivity, and of the ways apes have adapted to their lives in an environment radically different from that of their wild relatives. This unique look at zoos and animals is highly annotated, leading interested readers to further exploration, yet also extremely accessible for the more casual reader. »

Booklist, April 2016

SUMMARY

Introduction

1. The Ménagerie of the Jardin des Plantes

2. Growing Up Among Humans

3. Living at the Zoo

4. An Orangutan Who Can Tie Knots

5. On the Aesthetic Sense in Great Apes

Epilogue

Editeur : http://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/W/bo18889815.html

Voir le livre sur Amazon : http://www.amazon.com/Wattana-Orangutan-Paris-Chris-Herzfeld/dp/022616859X/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1460522635&sr=1-1&keywords=Wattana

CONTENTS

Introduction

Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey were part of the first researchers to have led long-term field studies on great apes at the beginning of the 60s. Because of their extensive stay in Africa, they were able to describe dimensions until then unknown about the lifestyle of apes: relationships between mothers and their youngs, the use of tools, and the transmission of knowledge from generation to generation. These two scientists have also demonstrated that great apes had unique life stories and different personalities. Primates that currently live in zoos generate a lot less interest than the ones studied in their natural habitat. Few scientific studies have been generated on them. However, they also possess traits of specific characters, form families, and use tools. The author brings great apes in captivity out of the dark and narrates their daily lives. She describes their fascinating behaviors, as well as, their strategies and their unique creativity in order to « make a living » and establish a « home » in our human world. This biography is based on field studies and scientific data. It allows the reader to discover a singular specie, the orangutan, through a fully original approach. Furthermore, this biography connects several stories ; the history of the Ménagerie of Paris, the stories of great apes that have succeeded each other in zoological parks, and the history of relationships between humans and their nearest cousins since the ancient times.

Chapter 1 The Menagerie of the Jardin des Plantes

Founded in 1794 and linked to the Muséum of Natural History of Paris, the Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes is one of the oldest zoos in the world, with the Austrian zoological park of Schonnbrun created in 1752 (but only made public later on). During the French Revolution, King Louis XVI’s menagerie, in Versailles, was raided. Only a few animals survived. The remaining ones were brought to the Jardin des Plantes, with other different animals seized from street merchants, then considered dangerous for the public order. The Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes was introduced, not only as a decorative garden, but also as a possibility for the public to see rare animals, while the scholars could study them in the middle of Paris. The first orangutan arrived in 1836 at the Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes, and the first chimpanzee came a year later. The lodge created for apes and monkeys, where Wattana will live in in 1998, was built in 1934. The idea of collection dominated until 1960 to 1970: the animals of the Ménagerie constituted a living collection, complementing the zoological collections of natural history; composed of skeletons, naturalized specimen, anatomic elements, etc. It was followed by plans involving the breeding of captive species in order to preserve their gene pool. This approach incited the transfer of great apes from one zoo to the other; causing the separation of family members, and the breaking-up of contact between certain individual and their keepers. Later, the people in charge of zoological park have, nonetheless, also tried to improve the living conditions of their guests, sensible at the increased public awareness in regards to animals.

Chapter 2 Growing Up Among Humans

The second chapter retraces Wattana’s life story : her birth in 1995 at the Zoo of Antwerp, her mother’s reject, and her education by the keepers. The little orangutan was then transferred to Stuttgart at the age of three months. Wattanna was entrusted to a human surrogate mother who took care of her with tremendous kindness until the age of two and a half years old. The raising of young apes by humans was very common around that time. In the wild, the little apes learn all the knowledge necessary to live in the woods, by observing and imitating their mother and fellows. Throughout their extensive childhood, they acquire habits, social abilities, skills, and knowledge connected with their habitat, as well as, traditions and culture distinctive of their geographic group. This way, they learn to « become-ape ». The captive environment is, on the other hand, much less vibrant than the natural environment. The knowledge gained by the primates is, therefore, limited, causing the inexperienced ones to lack examples to imitate, especially in motherhood. Not having learned « how to be a mother », in close relationship to humans and often too young, some females desert their baby. Captive apes attempt, nevertheless, to recreate an existence for themselves in the environment imposed on them. Relocated in Paris, Wattana built interspecies friendships with some of her keepers. She established bonds with other orangutans from the Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes. In August 2005, she gave birth to a female named Lingga. However, like her mother (who didn’t take care of any of her four babies), Wattana didn’t express any interest in her daughter.

Chapter 3 Living at the Zoo

The beginning of this chapter presents several famous cases about the first encounters between humans and orangutans. The first one arrived in Europe in 1776 was a young female that was brought to the menagerie of Guillaume V, Prince d’Orange-Nassau. In 1808, an orangutan shared the table of the empress Joséphine, wife of Napoléon. At the beginning of the 20th century, William Hornaday, director of the Central Park Zoo of New-York, described the remarkable behaviors of two orangutans from the park. In 1977, the talking-ape Chantek, raised by the anthropologist Lyn Miles who treated him like her son, learns how to go to the bathroom, tie knots, and makes objects that Miles qualifies as art & craft.

From the beginning of the 20th century, about three thousand orangutans were taken in western zoos. Today, they are over a thousand, of which 90% were born in zoos. A large amount of great apes are, therefore, forced to integrate human environments, differing greatly from forest environments in which they have evolved in for millions of years. It is important for them to be able to « elaborate a life » for themselves, to create a « being-at-home, » and to determine a territory in the locations assigned to them. They determine their territories by imposing their marks, their signature, their print and their traces, and through the occupation of precise spaces in their enclosure, the order in which different elements are placed, their feces or spits, the stripes traced on metal plates, the knotted fabrics on the rings and the beams of their cages, and the cleaning of the windows with some fabrics given by the keepers. They acquire astonishing know-how observed around their human companions that are then imitated. Great apes show a fascinating behavioral plasticity and flexibility, by borrowing our gestures, habits, skills, tools, and techniques. It is not a servile or grotesque imitation of man, but a real appropriation of know-how and elements of the human culture. Some great apes even changed their type of locomotion and became bipeds. Other ones use Ipad, or watch TV. It is, therefore, important to offer them various opportunities and to enrich the environment where we forced them to spend their existence in.

Chapter 4 An Orangutan Who Can Tie Knots

Wattana is the perfect example of the skills’ transmission, from humans to primates. She is one of the rare apes able to tying knots. Ethologists have, for a long time, believed that tying knots was a skill proper to man. However, dozens of apes, all living in close proximity to humans, demonstrate that they can make knots. This chapter, therefore, reviews the question of great apes’ knot-tying ability, rarely studied in primatology. How did Wattana learn to tie knots? She first observed closely how the keepers proceeded. She then attempted to imitate their motions and progressively started to integrate the sequence of movements to follow. Observation and imitation are, indeed, the base of learning concerning the great apes. Wattana has gradually assimilated this particular technique, and implemented it as soon as she was in the possession of rope, practicing and experimenting the different possibilities of tying knots. She seems to experience a certain jubilation from knotting; this pleasure has probably motivated her to produce more knots. By increasing her practice, she progressively became an expert at tying knots. The sequence of gestures proper to that type of subtle manipulation is certainly linked to the sylvan skills, notably, the techniques necessary to build nest : weaving, braiding, intertwining, twisting. As remarkable « practitioners » of the forest, the orangutans are like the other great apes, more « fibers-users » than « tool-users ». Several knots-tying apes are known: Nueva in Tenerife and Meshie in New York, in the beginning of the XXe century. In United States, throughout the sixties, some of talking-apes had the ability to tie knots and the author found a dozen other captive apes capable of the same skill. Regarding this study, the accounts of the keepers have been essential. Indeed, the keepers share the great apes’ everyday lives, sometime even a large part of their lives, and have, therefore, the capability to describe behaviors that are unnoticed by many.

Chapter 5 On the Aesthetic Sense in Great Apes

Certain of Wattana’s knotted creations clearly show that it does exist what we name an « aesthetic sense » in the great apes’ world. Several primatologists believe that the anthropoids like to « make art ». It is the case of the « painting-apes », among which the chimpanzee Congo, has produced over several hundred of paintings and drawings that have a very distinguishable style. While we have generally refused to recognize the esthetic sense of animals, numerous species generated creations that we could qualify as « artistic ». Some elephants have demonstrated real talent by tracing very subtle drawings. Many songs of sparrow birds are extremely complex, harmonious, and include many similar characteristics found in human melodies. The dolphins of Hawaii conceive impressive bubble rings through high levels of creativity and the technique implemented. The bowerbirds built magnificent nuptial bower. They play on optical illusions and combine thousands of elements carefully selected, peculiarly according to their colors. These exuberant and varying productions of different species seem to be manifestations of a vast and vital symphony, each resonating with the other ones.

Epilogue

This biography of Wattana points out that the story of individuals that we regroup under the name « orangutan » is not limited to a natural and phylogenetic history. They also possess a personal and social history, as this book attests it. The captive apes develop strong bonds with their relatives, interspecific friendships with keepers and various relationships with handlers, veterinaries, or visitors, present at the zoo. This biography is also related to a cultural history since captive great apes are constantly surrounded by our objects and our customs, they adopt our habits, and learn techniques specific to our societies. Therefore, great apes fall within histories that are specifically human: the history of Western colonization, the history of zoos, the history of relations between men and apes, the 18th century social and economic changes, and the industrial revolution of the 19th century. The intertwining of these different histories, forces us to open ourselves to a complexity generally forgotten, concerning « the animal ». Beside, in captivity, anthropoids use human abilities, while still transforming them to adopt their needs. They appropriate diverse human know-how. Wattana’s interest for these know-hows, her passion for our tools, and her capacity to adopt certain skills, touch us deeply. Therefore, this book has attempted to put forward the essential community shared by different living species. Wattana’s knots, the dolphins’ bubble rings, the birds’ songs, and the bowerbirds’ bowers attest the vibrant existence of all the beings, who, through their fascinating productions, constitute of a real re-enchanting of the world: the « ways to transfigure life is given by life itself. »

<< Back

|